|

Landing

Craft Flak.

Providing Anti-Aircraft Cover for the Invasion Fleet

Background Background

Landing

Craft Flack (LCF) were converted Landing Craft Tank (LCTs) with the front ramp

welded in position and the hold decked over as a platform for the guns. There

were a number of variants (Marks) but most were around 150/200 ft long with a

beam of around 30/40 ft.

[Photo;

LCF 37, tied up.

Not the author's craft but similar. © IWM (A 19420)].

LCTs were designed to carry tanks and heavy transport, while the LCFs were equipped with anti-aircraft guns to provide air cover for

the invasion fleet, particularly the troop carrying Landing Craft Assault (LCA)

flotillas, which were poorly equipped to defend themselves against air attack.

Telegraphist,

Hector Holland's light-hearted,

tongue in cheek commentary belies the hazardous situations he found himself in,

when death and destruction were his companions on

occasions. This is his story.

Generally speaking, the lower deck of His Majesty’s Royal Navy can be split

into two main types of sea-going animal life, viz., ‘Big-ship’ sailors and

‘Small-ship’ sailors. ‘Big-ship’ sailors are those poor, weak minded facsimiles of seamen, who serve

on battleships, cruisers, aircraft carriers and the like, whilst ‘Small-ship’

sailors are the hard-drinking, hard-working, hard-headed heroes, who made the

world safe for democracy. The men of the destroyers, sloops, frigates and

corvettes etc., were as decent a band of rogues, thieves and vagabonds as

ever picked a pocket, or slit a throat…needless to say, I was a ‘Small-ship’ matelot!

First Posting

I joined my first ship only three weeks after entering the service and said

goodbye to her only four weeks later. She was a sloop, which is something

between a destroyer, a prefab and a Japanese banana boat, built on the Clyde in 1917.

She was hardly the latest

thing in naval sea power and had the distinction of having a bomb dropped

down her after funnel at Dunkirk, from which she had never

quite recovered. I joined my first ship only three weeks after entering the service and said

goodbye to her only four weeks later. She was a sloop, which is something

between a destroyer, a prefab and a Japanese banana boat, built on the Clyde in 1917.

She was hardly the latest

thing in naval sea power and had the distinction of having a bomb dropped

down her after funnel at Dunkirk, from which she had never

quite recovered.

[Photo; the author in naval uniform].

She and I parted company one morning in mid-Atlantic, when part of the German

Underwater Brigade (U Boats) decided she had outlived her usefulness. They saved

the admiralty the trouble of scrapping her. She

went down in twelve minutes, taking my brand new No.1 suit, purchased

only three days before and a months ‘nutty’ ration (chocolate) which I’d been saving

for the kids back at home. So ended episode one of my naval career.

Landing

Craft Flak

Shortly after this, I

was ‘persuaded’ to volunteer for Combined Operations, where I was drafted to an

LCF. I arrived in Glasgow one cold, wet morning to join her at Barclay Curle’s yard. Never having seen

or heard of an LCF, I was prepared for almost anything. Despite this, I passed

by her three times, mistaking her for local bomb damage or some other

misfortune, when an

obliging dock worker pointed her out to me. The shock was so great that it was not

until I’d had my tot of Rum and rolled myself a ‘tickler’, that I could sit down

and calmly wonder what, in the name of the wee man, I had let myself in for!

She was long, thin and flat-bottomed with square bows and a blunt stern. Her

entire upper-deck bristled with gun-turrets, which bulged out on either side

like blisters. She looked like no other ship on earth and how she’d float and

maneouvre in rough weather caused me considerable worry from that day forward. She was long, thin and flat-bottomed with square bows and a blunt stern. Her

entire upper-deck bristled with gun-turrets, which bulged out on either side

like blisters. She looked like no other ship on earth and how she’d float and

maneouvre in rough weather caused me considerable worry from that day forward.

[Photo;

General view of the guns of an LCF.

The gun platforms protruded over the sides of the craft.

© IWM (A 19423)].

Every time we left port for the channel was an adventure, like going to sea for

the first time. I’d gaze longingly at the slowly receding coast, wondering if

I’d ever set foot on dry land again. To see her heading out to meet the Atlantic

rollers was indeed an awe-inspiring sight; she did not so much sail as ‘waddle’

in an ungainly manner, like a huge, grotesque duck! Her motion played havoc with

the cold, greasy atrocities, which masqueraded as meals.

One day,

a destroyer flashed us a signal as we wallowed in a

heavy sea, which read, ‘Please settle an argument. Are you a U-boat surfacing

or a trawler sinking?’... Just one of the many witticisms we had to endure during our

early days aboard.

Our crew consisted of sixteen seamen and sixty marines.

The purpose of the latter was to man our four double pom-poms and ten, double

barrelled, Oerlikons. Our craft was many times smaller

than a corvette, which carries a crew of eighty or thereabouts. The cramped, overcrowded conditions on board

our LCF was such that if someone hiccupped during the night, the man two hammocks

away would probably say ‘excuse me’ and someone on the other side of the

mess-deck would likely fall out of bed!

Our cooling system

in the summer was a very small porthole about the size of a fully grown cabbage.

In the winter, our heating plant was a two bar electric fire about the size of a dog biscuit.

Its output could not have

toasted a slice of bread, let alone warm up our shivering carcasses or thaw out

our frozen clothes after four hours on the open bridge. How I blessed my tot of

‘grog’ and looked forward to the most popular ‘pipe’ in the navy…’Up Spirits’.

Every day, at twelve o’clock, it transformed me from two yards of frozen pump

water to something resembling a human being!

My rating in the navy was

‘telegraphist’, commonly known to the other branches as ‘sparkers’ or

‘comic-singers’. There was no provision whatsoever for a wireless cabin aboard

this floating sardine tin, since none was considered needed in the original LCT

design. By the time their lordships discovered their mistake, the craft were already

well under construction. When wireless communications were being used, I found

myself squeezed into a corner of the wheelhouse, between the compass and the

wheel, with a wireless set jammed between my knees while seated on an upturned bucket. How I hated

the sight of that bucket and the mark it left on my tender posterior! My rating in the navy was

‘telegraphist’, commonly known to the other branches as ‘sparkers’ or

‘comic-singers’. There was no provision whatsoever for a wireless cabin aboard

this floating sardine tin, since none was considered needed in the original LCT

design. By the time their lordships discovered their mistake, the craft were already

well under construction. When wireless communications were being used, I found

myself squeezed into a corner of the wheelhouse, between the compass and the

wheel, with a wireless set jammed between my knees while seated on an upturned bucket. How I hated

the sight of that bucket and the mark it left on my tender posterior!

[LCF 20 crew duty roster, courtesy of Ian

Foreman].

Eventually

they fitted me out with a proper office,

complete with chairs, etc. They even sent me three more ‘sparkers’ to hang

around and make the place look untidy.

Preparations

for D-Day

For a long time we

undertook countless training exercises with LCTs, LCIs, LCAs,

LCGs, etc. in a long succession of ‘D’ days, ‘H’ hours and mock beach

assaults. Some bright spark ashore even organised a prolonged endurance exercise

for the communications ratings. For three days and three nights I sat in a

stuffy smoke-filled cabin, drinking

innumerable cups of ‘kye’ (tea) in a vain attempt to keep me awake. Signal

after signal came through until the Morse code became a meaningless jumble of

sound. I had to take a break for a few minutes or scream.

All our officers were RNVR,

so their knowledge of wireless telegraphy and

the organisation and structure behind it, was almost nil.

The

responsibility for all communications and signals, therefore, rested with me.

One early morning in June 1944, I was called to the skipper’s cabin and

instructed to close the door, the porthole, the ventilation hatch and my big

mouth! I was about to learn of

plans and developments

of great consequence, which I should

tell to no one.

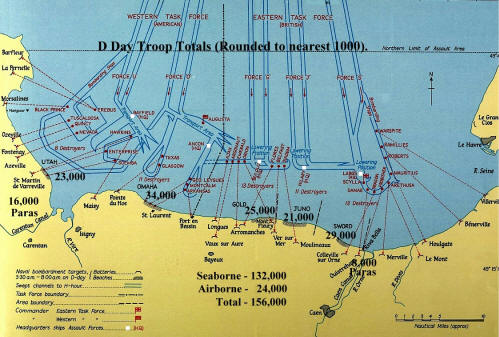

At approximately 5am, on the morning of June 4th,

we would ‘up kedge’ and set out from Southampton for the coast of France. At 0600 hours on the 5th,

we would cruise up and down the beaches of Normandy playing tag with the German

pill boxes and gun emplacements on the shore. However,

the meticulous detail formed a mountainous pile of closely typed documents, which

I was ordered to digest. It was important not to raise suspicions of the

impending operation, so I should lock myself in the wireless cabin. Operation Neptune, the amphibious phase of Operation Overlord

was only days away.

Maintaining the

secrecy in the manner proposed was more difficult

to accomplish than you might imagine. I had allowed my wireless cabin to be used by all and sundry as neutral

territory where: loafers could escape from the eagle

eye of the coxswain; gasping nicotine addicts could indulge in an illicit

‘tickler’ during non-smoking hours and lonely Romeos could pour out their hearts on

paper to their Juliet’s away from the din, banter and

leg-pulling of the mess deck, where gossip,

scandal and tit-bits were freely exchanged.

As if that wasn't enough, on HM ships it was well

known that all rumours and speculation originated in the W/T office... then

there were the opportunists, who would poke their snouts around the door to

enquire ‘What’s the latest buzz, Sparks?’

Our

W/T cabin was a busy,

unofficial information hub and to suddenly

revert to its intended exclusive

use for ‘comic singers’ would defeat the object of

the exercise. I had a

big problem on my hands and I knew it!

However, all was not lost, I asked the coxswain to place a notice on the mess deck inviting all ratings, with no duties,

to draw a paintbrush and pot of paint from the

stores and report to the W/T office

forthwith. Needless to say, I spent two

full days in almost complete seclusion, working out

the details of Operation Neptune as they affected us!

D-Day

As everyone knows now,

D-Day was postponed for 24 hours. We

arrived off Normandy on June 6th, where

we created a lot of noise but did

very little damage. The Luftwaffe mostly kept well out of

range or didn’t show up at all, perhaps due in

part to the reception they knew awaited them!

After a few quite boring weeks, we ran out of

fresh water and provisions and returned to Southampton

to re-stock. There were so many Yanks in town drinking what little beer

there was, eating what little food there was and finishing off the war

for us there and then. We were not sorry to leave for the beachhead again.

Things were very different on our return to Normandy. The Germans

were now trying to break through our defensive cordon of craft around the beachhead.

It was vital to protect the supply ships as they discharged thousands of tons of

desperately needed vehicles, munitions and supplies for the

advancing armies ashore. Any break in the

supply chain might give the enemy a chance to regroup and counter attack.

We became part of ‘the Support Squadron, Eastern Flank’.

During daylight hours we patrolled around the beachhead but, at dusk,

we anchored off the

enemy held part of the coast, forming a line out to sea. The object

was to detect and destroy midget submarines,

human torpedoes,

and Explosive Motor Boats (EMBs), as they tried to

penetrate the line.

The EMBs

could do forty knots and were packed with high explosives. They were remotely controlled by a

parent ship but each carried one man,

who aimed the craft on its final approach

to its target

before jumping into the sea, with very little chance of being picked up. We

were not allowed to move from our position under any circumstances,

even when our searchlights picked out a dozen or so EMBs

heading straight for us. Fortunately, such was the

intensity of our collective fire power that we always managed to blow

them up at a safe distance.

The

midget submarines and human

torpedoes were, however, a different proposition entirely.

We could not hear them and

they were difficult to spot with only a little Perspex observation bulb above water.

Several

of our craft in line were

blown up with no warning whatsoever.

Looking for survivors was futile. Our only consolation was that no

midget submarine ever escaped after attacking a craft.

Jerry

also laid mines from the air just ahead of our positions. On the flow, the tide

carried them past us during the night, entangling themselves in our screws and

kedge wires. On the ebb, the tide carried them back again in the morning. As

some craft pulled in their kedge

anchors or engaged their

propellers on

starting up their main

engines, they simply disappeared in the midst of a high

explosion.

The

hazards we faced at that time also included shells fired from long-range shore batteries,

guided by feedback from forward observation positions . We

regularly moved around, sufficient to prevent them

from

homing in on our positions. The boredom we felt on our first visit had been

replaced by concerns about these many hazards . However, after the individual Allied

beachheads joined up and pushed the Germans inland, this intense activity decreased

and we survived to fight another day.

Walcheren Walcheren

There was a German

garrison of 10,000 on Walcheren that was proving very difficult to

dislodge. With their heavy guns overlooking the estuary to the River Sheldt,

they prevented the Allies from using the port of Antwerp,

already in their hands, to supply their armies

as they fought their way towards Berlin.

In

November 1944, an amphibious raid took place during which we lost eight craft out of ten

from our flotilla. The German gun

emplacements concentrated their fire on our LCFs, while the Commandoes

slipped ashore unmolested. We were told it was good strategy but it

was very difficult for us to

accept.

Our

little shells simply bounced off the ten feet thick

concrete walls protecting the Jerry guns, while

our craft were systematically blown to pieces

by their big guns; one shell for'ard, one

shell aft, one shell amidships...

another one to Davy Jones’s locker.

There’s was nothing we could

do about it, because we had been

ordered to stay on station. Still, I

suppose, there must have been a reason for it in the

big picture of the war. Anyway,

the Sunday papers

made a big splash about it and we all donated something to build a memorial to

the blokes who didn’t make it.

It was a successful

operation and Allied supply ships were soon unloading their vital cargoes much

closer to the front. 6 months later the war was over. Full story of

Operation Infatuate here.

Last Posting

Shortly after returning to the UK, I had a spell in hospital. On

discharge I was to rejoin my LCF but its whereabouts was

unknown. The powers that be advised, ‘get a ship at Tilbury docks and see if you can find

her anywhere on the other side’. I had a very enjoyable trip

through France, Belgium and Holland, taking in most of the principle towns and

cities on the way. I finally traced her to a canal at 03.00 hrs

in a small Dutch village called Wemeldinge, in North Beveland,

not far from Walcheren. The rain was teeming down and the bank of the canal

was a sea of mud.

It was an odd sight to see the white ensign sticking up

in the middle of a village miles away

from the sea.

We

were now attached to the Marine Commandoes for as long as they required us and

our officers.

Most of the crew had grown beards to distinguish themselves from the ‘Land

Service’ Marines. We encountered German ‘frogmen’ there, who were

attempting to destroy canal lock gates and to block the shipping

lanes of the Scheldt Estuary.Their aim was to paralyse the port of

Antwerp, then under a constant hail of V2

rocket bombs. We

were now attached to the Marine Commandoes for as long as they required us and

our officers.

Most of the crew had grown beards to distinguish themselves from the ‘Land

Service’ Marines. We encountered German ‘frogmen’ there, who were

attempting to destroy canal lock gates and to block the shipping

lanes of the Scheldt Estuary.Their aim was to paralyse the port of

Antwerp, then under a constant hail of V2

rocket bombs.

[Photo; the author,

Hector Holland, at the

50th anniversary commemorations at Walcheren in November 1994].

The

frogmen swam over to our territory from an island

called Scowen, about half a mile away.

They were a constant nuisance, as were parties of SS troops, who would steal ashore

in the middle of the night and grab a couple of sentries or Dutch civilians for questioning.

The original reason for our being there was, I

believe, to take Scowen,

but a couple of attempts fell through. Anyway, the war in Europe finished and we returned

home to pass the time knitting and growing

flowers until we were demobbed. All in all, it was nothing if not interesting but, don’t think it hadn’t

been fun…because it hadn’t!

"There is no glory in war... only death,

destruction, shattered bodies and disturbed minds."

Further Reading

On this

website there are around 50 accounts of

landing craft training and

operations and landing craft

training establishments including the incredible story of

LCF 7.

There are around 300 books listed on our 'Combined Operations Books' page which can be

purchased on-line from the Advanced Book Exchange (ABE) whose search banner

checks the shelves of thousands of book shops world-wide. Type in or copy and

paste the title of your choice or use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions.

There's no obligation to buy, no registration and no passwords. Click

'Books' for more information.

Correspondence

Hi Geoff

My grandfather gave me the badge/emblem from

his WW2 Landing Craft LCLF21 (Landing Craft

Large Flak) which formed part of the Trout Line. My grandfather gave me the badge/emblem from

his WW2 Landing Craft LCLF21 (Landing Craft

Large Flak) which formed part of the Trout Line.

My grandfather is still alive and his war

memories are amongst the easiest for him to recall !!

Cheers

Jamie Cook

Acknowledgments

This account of life on a WW2 Landing Craft Flak was written by

Hector

Holland and published here with the kind permission of the author's son,

Ian Holland. This account of life on a WW2 Landing Craft Flak was written by

Hector

Holland and published here with the kind permission of the author's son,

Ian Holland.

|

I joined my first ship only three weeks after entering the service and said

goodbye to her only four weeks later. She was a sloop, which is something

between a destroyer, a prefab and a Japanese banana boat, built on the Clyde in 1917.

She was hardly the latest

thing in naval sea power and had the distinction of having a bomb dropped

down her after funnel at Dunkirk, from which she had never

quite recovered.

I joined my first ship only three weeks after entering the service and said

goodbye to her only four weeks later. She was a sloop, which is something

between a destroyer, a prefab and a Japanese banana boat, built on the Clyde in 1917.

She was hardly the latest

thing in naval sea power and had the distinction of having a bomb dropped

down her after funnel at Dunkirk, from which she had never

quite recovered.